Gluten can cause problems for some people with weak digestive systems like the elderly and special needs children (Sumath et al. 2020). Thankfully a gluten-free diet can help (Quan et al. 2022). Also see “Is Gluten Triggering Your Symptoms?“, and “Gluten and Autism“.

Gluten makes the texture of bread and pasta sticky, chewy, and thus more enjoyable. Many children certainly love their bread and pasta. Thankfully they can still enjoy these foods with so many gluten-free alternatives available today.

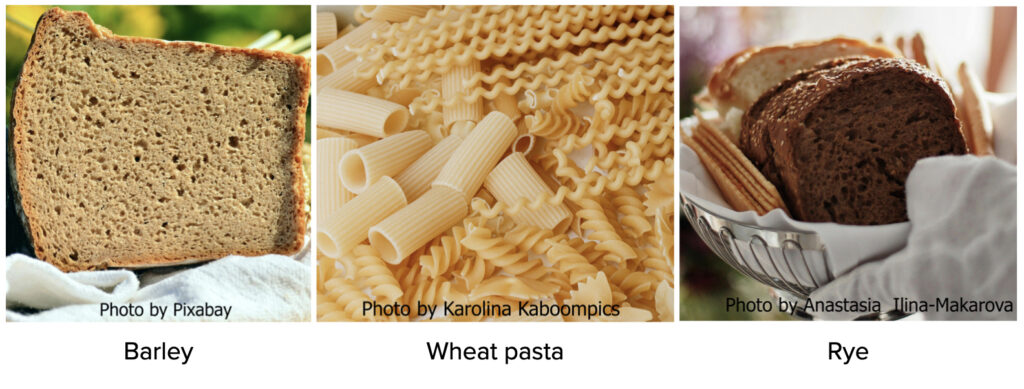

Gluten Grains

Most bread, pasta, biscuits, cookies, cakes, croutons, and pizza dough contain gluten. Gluten sources are wheat (including wheat varieties like semolina, spelt, graham, and durum), barley, and rye.

Gluten-free Alternatives

Gluten-free flour substitutes are from grains like rice, corn, and buckwheat. Root crops like potato, sweet potato, cassava, and arrowroot are also good gluten-free substitutes.

Gluten-free noodle substitutes are made of rice or corn flour. There are many other gluten-free noodle alternatives in the Asian market such as Pad Thai (made of rice), Vietnamese rice noodles, Korean glass noodles (made of a root crop), mung bean vermicelli, and bee hoon (made of rice).

Glutenous rice is gluten-free. Although it has a sticky texture and thus its name, glutenous rice does not have gluten protein.

Oats do not contain gluten but may be contaminated in facilities that process gluten grains. However, oats also have another protein, avenin, which may trigger immune responses similar to gluten-sensitive individuals.

Hidden Sources of Gluten

Wheat is used in many food processes so it is important to check labels for hidden sources of gluten.

Wheat flour helps seal in flavor so it is used even in flavored snacks that could otherwise be gluten-free like nuts and chips.

Wheat may be used to thicken sauces like gravy or salad dressings.

Malt is usually made of gluten grains like wheat or barley. They are brewed to make beer, soy sauce, malt syrup, and seasonings.

Potato chips and multigrain tortilla chips may have added wheat flour.

Meat substitutes may utilize gluten to create the stretchy texture of meat. Processed meats add wheat as extenders.

Burger patties and meatballs may add wheat or bread for a softer texture.

Fried foods usually add bread crumbs for the extra crunch.

What to expect from a Gluten-free diet

A review of several scientific studies has seen that a gluten-free diet and casein-free diet improve brain fog and cognition of children in the spectrum (Quan et al. 2022).

Health improvements are also observed when gluten is removed from the diet of patients with autoimmune conditions such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (Piticchio, et al. 2023) and rheumatoid arthritis (Bruzzese et al. 2021).

It takes 3 weeks for the body to purge gluten. Thus a gluten-free diet should be done for at least 4 weeks. Symptoms that can be alleviated are those associated with gluten sensitivity including bloating, digestive issues, brain fog, fatigue, or autoimmune symptoms. See “Is Gluten Triggering Your Symptoms?”

References:

1. Sumathi, T., Manivasagam, T., & Thenmozhi, A. J. (2020). The Role of Gluten in Autism. Advances in neurobiology, 24, 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30402-7_14

2. Quan, L., Xu, X., Cui, Y., Han, H., Hendren, R. L., Zhao, L., & You, X. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the benefits of a gluten-free diet and/or casein-free diet for children with autism spectrum disorder. Nutrition reviews, 80(5), 1237–1246. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuab073

3. Piticchio, T., Frasca, F., Malandrino, P., Trimboli, P., Carrubba, N., Tumminia, A., Vinciguerra, F., & Frittitta, L. (2023). Effect of gluten-free diet on autoimmune thyroiditis progression in patients with no symptoms or histology of Celiac disease: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in endocrinology, 14, 1200372. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1200372

4. Bruzzese, V., Scolieri, P., & Pepe, J. (2021). Efficacy of gluten-free diet in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Reumatismo, 72(4), 213–217. https://doi.org/10.4081/reumatismo.2020.1296